Chalkbrood Disease, caused by the fungal pathogen Ascosphaera apis, is one of the most common and frustrating brood diseases encountered by beekeepers worldwide. While rarely fatal on its own, a heavy infection can severely weaken a colony by reducing its population of nurse and field bees, impacting honey yield, and leaving the hive vulnerable to other, deadlier pests. Mastering the identification, prevention, and treatment of Chalkbrood Disease is essential for maintaining the health and productivity of your apiary.

This comprehensive guide delves deep into the life cycle of the Ascosphaera apis fungus, explains the exact conditions that favor its spread, and outlines an integrated management strategy using both cultural techniques and approved treatments to protect your hives.

Understanding Chalkbrood Disease: The Fungal Pathogen

Chalkbrood Disease is a fungal infection that specifically targets the larval stage of the honeybee.

The Causative Agent: Ascosphaera apis

- Ascosphaera apis is a microscopic, spore-forming fungus. Unlike bacterial diseases, this fungus thrives in cool, damp conditions.

- Mode of Infection: The infection starts when a larva ingests fungal spores present in its food.

- Fungal Development: The spores germinate inside the larva’s gut. The fungus then begins to grow rapidly, invading the larval tissue and eventually penetrating the entire body, causing death.

Early Detection is Key

Managing Chalkbrood Disease starts with a thorough inspection. To spot the “mummies” early and maintain hive hygiene, you need high-precision Beekeeping Tools and protective gear.

- Stainless Steel Hive Tool: For scraping infected frames.

- High-Quality Smoker: To calm bees during disease checks.

- Hygienic Monitoring: Essential for tracking colony health.

The Susceptible Stage

The most susceptible stage is the pre-pupal stage, just after the larva has spun its cocoon and been capped. The fungus consumes the larva, causing it to harden and turn into a characteristic, rock-like mass, which is often called a “mummy.”

The Hallmarks of Chalkbrood: Symptoms and Diagnosis

Proper diagnosis is crucial because Chalkbrood Disease can sometimes be confused with other brood problems like European Foulbrood (EFB).

The “Mummy” Sign

The definitive symptom of Chalkbrood Disease is the presence of chalkbrood mummies.

- Appearance: Dead larvae and pupae dry out completely, becoming hard, brittle, and chalky white or gray-black masses that perfectly fit the shape of the cell.

- Color Coding:

- White Mummies: Indicate the fungus has completed its asexual cycle. These are most commonly seen.

- Black/Gray Mummies: Indicate the fungus has entered its sexual reproductive stage and is producing dark, infectious spores (Ascospores).

- Location: Mummies are often found within open or capped cells, but the clearest sign is seeing these white or black pellets on the bottom board or just outside the hive entrance (workers recognize them as foreign bodies and attempt to remove them).

Brood Pattern and Smell

- Brood Pattern: Unlike American Foulbrood (AFB) which causes a dark, ropey, foul-smelling mass, Chalkbrood causes a scattered or spotty brood pattern.

- Smell: Chalkbrood Disease generally does not produce a distinct foul odor, though a very heavy infection might have a faintly musty or moldy smell.

The Ecology of Chalkbrood: Predisposing Factors

Understanding why a colony gets Chalkbrood Disease is the key to prevention. The primary triggers are related to stress, environment, and genetics.

Environmental Triggers (The Cold and the Damp)

- Temperature and Humidity:Ascosphaera apis spores germinate best in conditions of low temperature and high humidity.

- Ideal Spread: This often occurs during extended periods of cool, wet weather in spring or early summer, when the colony cannot maintain optimal brood nest temperature (35C or 95F).

- Ventilation: Poor ventilation and a damp environment inside the hive contribute significantly to fungal growth.

Colony Stress and Genetics

- Small or Weak Colonies: Small colonies (like new splits or packages) struggle to cover and heat the entire brood area, making them highly susceptible.

- Queen Quality: A poor or aging queen leads to a scattered brood pattern, further complicating the maintenance of thermal regulation.

- Hygienic Behavior: A crucial genetic factor. Highly hygienic bees rapidly remove diseased or dead brood (including mummies), preventing the spread of spores. Colonies with low hygienic behavior are much more prone to chronic infection.

Integrated Management Strategies for Chalkbrood Disease

The best defense against Chalkbrood Disease is not chemical treatment, but proactive hive management and genetic selection.

1. Cultural and Environmental Control

These non-chemical methods should always be the first line of defense:

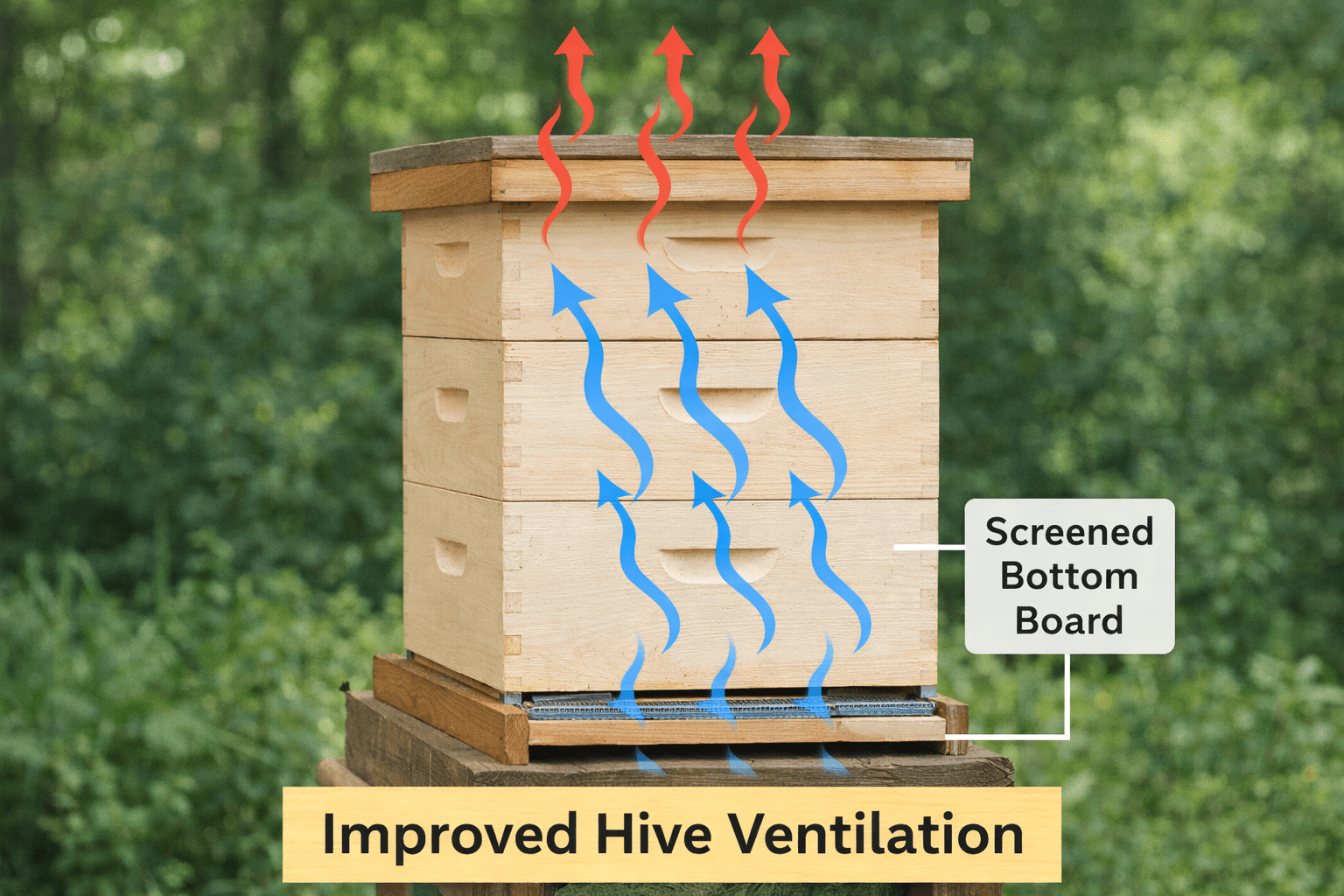

- Improve Ventilation: Use screened bottom boards (SBBs) to increase airflow and reduce moisture accumulation. Ensure the hive entrance is wide enough.

- Warmth and Sun: Ensure the apiary is located in a sunny area that receives morning sun, helping the colony warm up quickly. Reduce the entrance size during cold spells to help heat retention.

- Reduce Brood Size: If the colony is weak during a cold snap, temporarily reduce the brood area with a follower board to allow the bees to heat the smaller space effectively.

- Remove Mummies: Scrape the bottom board to remove any mummies and prevent workers from spreading spores further.

2. Genetic Solutions (Requeening)

- Requeening: This is the most effective long-term solution. Replace the current queen with a queen from stock known for high hygienic behavior (often tested and certified).

- Boost Population: Requeening with a young, prolific queen rapidly increases the colony size, allowing bees to cover the brood area more effectively and maintain temperature/humidity control.

Chemical and Supplemental Treatments (When Necessary)

Chemical treatment is generally a last resort for Chalkbrood Disease, as the fungus responds better to cultural methods.

Approved Treatment Options

Currently, there are no EPA-approved antibiotics or fungicides specifically for treating Chalkbrood Disease that are widely recommended due to limited efficacy and potential residue. The most common recommendation remains strengthening the colony and requeening.

- Avoid Overuse of Antibiotics: Some beekeepers mistakenly use Terramycin, which is designed for bacterial diseases (like AFB/EFB) and is ineffective against the Ascosphaera apis fungus.

Nutritional Support

- Pollen Patties: Provide high-quality nutritional supplements (pollen patties or substitutes) to boost the nurse bee population and overall immunity, helping the colony overcome stress.

Strengthen Your Hive: High-Protein Pollen Substitute

A colony battling Chalkbrood Disease or spring buildup requires peak nutrition. Our selected High-Protein Pollen Substitute provides the essential amino acids nurse bees need to boost the colony’s immune system and stimulate rapid growth.

Shop Pollen Patties on Amazon »As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

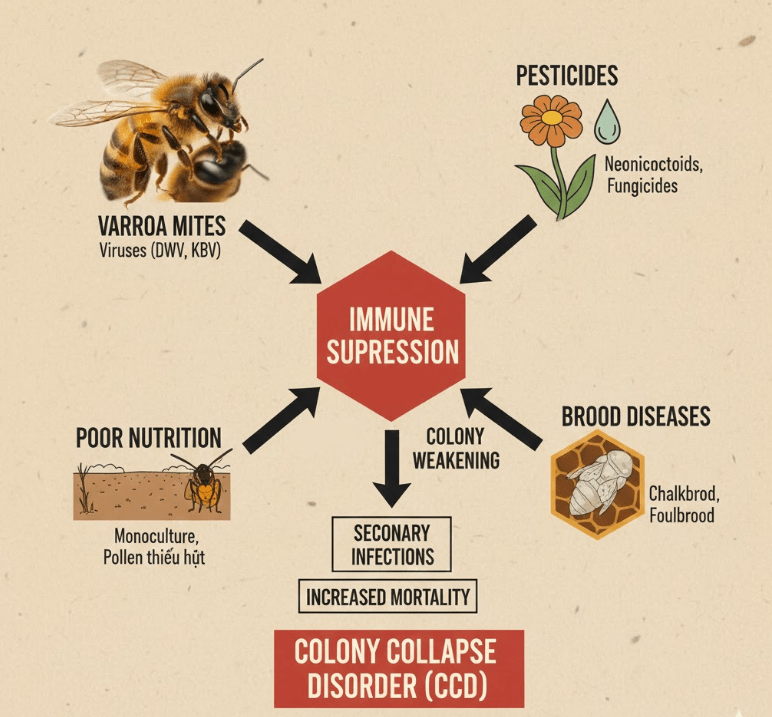

The Interplay with Varroa Mites and CCD

While Chalkbrood Disease itself is not the primary driver of Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), it significantly weakens the bee’s immune system, creating a gateway for deadlier pathogens.

- Varroa Mites: The mites act as vectors, often carrying and transmitting viruses. A bee weakened by fungal infection is less resilient to mite-transmitted viruses (like DWV).

- Stress Multiplier: A colony simultaneously dealing with cold stress, poor nutrition, high Varroa levels, and Chalkbrood infection is overwhelmingly likely to collapse. This underscores the need for effective Varroa Mite Control as a necessary preventative measure against all secondary infections.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Chalkbrood Disease

Chalkbrood is rarely the direct cause of colony death. However, it severely weakens the colony by reducing the emerging population, making the hive highly susceptible to collapse from cold, Varroa-transmitted viruses, or starvation.

Yes. Chalkbrood is a fungal disease specific to bee larvae and does not affect the safety or quality of the honey consumed by humans. However, if the infection is heavy, honey production will be minimal.

Often, yes. As the weather warms up, humidity drops, and the colony population expands, the bees can typically ‘clean up’ the infection on their own. However, if the queen is poor or the hygienic behavior is low, the infection can become chronic.

Requeening with a young queen from a lineage known for strong hygienic behavior is widely considered the most effective long-term solution, as it addresses the underlying genetic and population weakness.

Conclusion: Managing the Chalky Threat

Chalkbrood Disease is an endemic challenge in beekeeping, often serving as a barometer for the colony’s overall health and the efficacy of the beekeeper’s management practices. By understanding that this is primarily a disease of weakness and environment—thriving in cool, damp, stressed colonies—the solution is clear.

Focus on cultural control: improve ventilation, ensure proper nutrition, and be proactive about requeening with genetically hygienic stock. By strengthening the hive’s natural resilience, you minimize the risk, outgrow the infection, and ensure your colonies remain robust and productive, ready to withstand the many challenges of the modern apiary.

🐝 A Century of Beekeeping Wisdom

"Beekeeping is more than a hobby for me—it’s a family legacy. From my great-grandfather to my brother and me, we’ve managed our apiaries in the rugged landscapes of Herzegovina for four generations. Today, we care for over 300 hives, blending century-old traditions with modern techniques. Every tip I share comes directly from our hives to your screen."